It’s finally here; the first episode of the Lifting the Iceberg podcast! I sit down with Alexa Spaddy to talk about the logo for this podcast which she designed. Through talking about this piece, I explain some of my core interests that I will be exploring on this show, as well as talking with Alexa about her creative process with bringing this design into being. Enjoy!

Having, Being and the Psychedelic Experience

“Man has set for himself the goal of conquering the world but in the process, loses his soul.”

-Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

We want more. More property, more money in the bank, more cars, more movies, more shoes, more houses, and more status symbols. Modern society can be characterized by its constant generation and consumption of material possessions; but where do these possessions go when they are discarded? This is an important question to ask, as a society that has an endless appetite for more material possessions will be inevitably balanced by an equally endless production of waste. The answer; the natural environment. When material goods are discarded, only a small percentage of those goods end up being recycled. The rest is funneled into landfills, but that’s only when it is responsibly and conscientiously managed. An untold amount of garbage subsequently ends up in the natural environment, leading to ecological devastation. CNN recently reported that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a floating patch of plastic debris and trash, is now “three times the size of France”. But, this problem is not as simple as finding a better solution for managing waste, nor is it the simple act of “cleaning up” the pollution and ecological devastation that has already occurred; that is treating the symptom, not the cause. Something needs to change, and though this seems to emerge as an ecological problem, it is more deeply and appropriately dealt with as a psychological one. This paper will outline the problem of modern Man’s materialistic inclinations through the psychological lens, borrowing from the insight of the humanist psychologist Erich Fromm, and provide a solution based on empirical data; the controlled and responsible consumption of psychedelic substances.

“If I am what I have, then I lose what I have, what then am I?” asks Erich Fromm, the influential German psychoanalyst in his book To Have or to Be? He was one of the first psychoanalysts to study and diagnose the problems of Man as they relate to the destruction of the natural environment. For him, the problem lies in a psychological mode of existence that is predicated on consumerism, materialism, industrialism, and a pathologically exaggerated value on having. Fromm insists that modern Man is perverted in his value structures, confusing having with being. Modern Man believes that “if I have much, I am much” . This fundamental axiom is juxtaposed with what Erich Fromm labels as the more proper psychological mode of Man; the mode of being. This is the modality of the psyche that finds identity in the non-material qualities of existence; of virtue, integrity, and an embodiment of knowledge and values. More on the being mode later. First, let us dive more deeply into the nature of the having mode, its sources, and the implications it has on for the natural environment.

The having mode, according to Fromm, is a mode of being reinforced by the premises of our modern, post-industrial age social organization. Our society is fueled by a promise; by what Fromm calls “The Great Promise of Unlimited Progress”. It is the promise of domination over nature, of material abundance, of the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people, and of unimpeded personal freedom; freedom to hedonistically and passively consume whatever one wishes for. This promise has held faith for countless generations. Though some of these values have always been held in some form, particularly the desire to conquer nature, Man was not able to fully realize any of this until the industrial revolution. During the industrial age, mechanical and nuclear energy substituted human and animal energy, the computer substituted the human mind, and our ability to produce began to make possible the idea of continual abundance for all. We were on our way to constant consumption. The industrial age began a conquest, but Fromm warns that “… our spirit of conquest and hostility has blinded us to the fact that natural resources have their limits and can eventually be exhausted, and that nature will fight against human rapaciousness”.

There are two pathological premises at the root of this Great Promise of Unlimited Progress, as Fromm asserts. One, that “the aim of life is happiness, that is, maximum pleasure, defined as the satisfaction of any desire or subjective need a person may feel (radical hedonism)”. Two, “that egotism, selfishness and greed, as the system needs to generate them to function, leads to harmony and peace” . These premises are largely what engenders the having mode. If happiness is consumption, then Man will continue to do so as far as he believes that happiness is an ultimate ideal. A person might even come to think that if they are not consuming, they are not or cannot be happy. If one cannot consume and meet the needs of all their desires and satisfactions, they will be left feeling hollow, unachieved, and impotent as a functional person in society. So, with this feeling of material and consummatory lack being defined as the opposite of happiness, Man will run away in the opposite direction; in the direction of constant consumption to procure the Great Promise’s definition of the ideal mode of being.

The first premise relates specifically to the consumption of material goods as it states that hedonistic pleasure is the source of happiness, and that form of pleasure can only be created by the sensory outlets of the body. One must consume food to have the pleasure from food; such is the nature of consuming cars, jewelry, drugs, sex, shopping. These are behaviors that offer pleasure in the short-term, as they gratify and satiate very baseline human drives such as relieving oneself from hunger or sexually gratifying oneself, but this form of pleasure is not a type that predicates itself at all on what is most beneficial in the medium to long-term future. That hamburger might taste good and be pleasurable now, but the deforestation of the Amazon jungle to have pastures to raise the beef from which the burger was made will have long-term consequences that will overshadow the small moments of pleasure offered by a hamburger. As long as happiness is put forth as the ultimate ideal, and as long as it is defined as consummatory freedom and hedonistic pleasure, it will place Man in a motivational state that maximizes the desire to consume material goods. This state might have positive short-term effects on well-being, but it is a bad medium to long-term strategy. If Man is to preserve the finite planet on which he lives, he needs to learn how to temper an otherwise infinite appetite.

The second premise of the Great Promise is that egoism, the ultimate concern for a bounded sense of identity excluding everything outside of the individual, is the most beneficial frame of mind for the individual and for the society. In other words, it is more important that I have than that you have or we have. This form of egoism says “if I have more, I am more”. Not only is this premise supported by our society, but it is necessary in order for the current system to function properly. It is here that a pathological aspect of this premise comes to the surface. This premise is based on the notion that what is best for the system at large is also what is best for the individual. The system thrives on a collective of greed-driven, egoistic people competing with each other to succeed in their efforts to create the most value for themselves. But, not only is what is most beneficial for the prevailing system not most beneficial for the individual, it is also not most beneficial for the natural environment. If we maintain ourselves as a species that has an infinite appetite based on our pathological sourcing of self-esteem and personal value, we will continue to consume the resources on the Earth, and destroy the natural environment from which we evolved.

So, how exactly do the central narratives of a social system, such as the Great Promise, influence the behavior and psychological modes of existence of the population? The answer; through a form of natural selection. A system will reward individuals for behaviors that aid in the growth of the system, and punish behaviors that go against the system. In this way, the society places selection pressures on behaviors and thoughts, and the evolutionary process leads to a converging of the collective psyche to a state that has been selected for as most successful. Our social system selects for mindsets in the same way that tall tree branches selected for the long neck of the giraffe. But, the having mode as it is produced by our society is not exclusively a top-down phenomenon. The individual and the society are in a feedback-loop, effecting the evolution of each other. When trying to change a system, the proper level to work from is the level of the individual. As Ghandi once said, “you must be the change you wish to see in the world”.

According to Fromm, adopting the being mode of existence is the crucial psychological transformation needed to avert our species from catastrophe. But, what is the being mode, and how is this mode more beneficial for the long-term success of our species as well as being beneficial for the health and preservation of the natural world?

The crucial difference in the having mode and the being mode lies in the way the focus of well-being lays within each mode. In the having mode, short-term gain is positioned above all else, leading to the guiltless depletion and discarding of natural resources. This mode is also characterized by an inherent narcissism, which Fromm describes as “an orientation in which one’s interest and passion are directed to one’s own person: one’s body, mind, feelings, interests… for the narcissistic person, only he and what concerns him are fully real. What is outside, what concerns others, is real only in a superficial sense of perception; that is to say, it is real for one’s senses and one’s intellect. But it is not real in the deeper sense, for our feeling or understanding. He is, in fact, aware only of what is outside, inasmuch as it affects him. Hence, he has no love, no compassion, no rational, objective judgement. The narcissistic person has built an invisible wall around himself. He is everything, the world is nothing. Or rather: he is the world.” This narcissistic orientation engendered by the having mode leaves the individual to be concerned only for their individual well-being, excluding the outside world, and subsequently the natural world. The being mode is concerned with not only the well-being of the individual, but the well-being of the collective species, as well as the world in which the individual lives, as it is evident when seeing reality through the being mode that the individual is inextricably related to the natural environment.

If we shift to the being mode, we would see that the having mode is a direct threat to our survival and our very ability to be in the first place. Man has become blinded to the destruction that he is causing to our planet, blinded by that fast, new sports car, by the crisp sound of a beer opening and by our new Hoover vacuum cleaner (a kind much better than the neighbors’). But, how can we shift our psychological orientation from the having mode to the being mode in time to avert a natural disaster? One solution could be the conscientious use of psychedelic substances.

Psychedelics are a class of drugs that includes LSD, psilocybin mushrooms and mescaline, that have been used in a medicinal context for up to ten-thousand years, and the use of these substances is potentially “as old as civilization itself” (Mckenna 30). The word psychedelic was first coined by a psychoanalyst named Humphry Osmond, and comes from a Greek-root meaning “to manifest the mind”. Psychedelics are a unique type of substance in that they are not physically addictive, their active compounds mimic endogenous neurochemistry, and are incredible safe. The Global Drug Survey recently listed psilocybin mushrooms as the safest of all scheduled substances. Psychedelics dependably induce what is known as a mystical experience. These mystical experiences as induced by psychedelics are colloquially known as the psychedelic experience. But, what does this have to do with shifting the psychological mode of Man into a mode that is more sustainable and beneficial for the natural world?

Evidence suggests that those who have used psychedelics have values and beliefs that differ from those who have never used psychedelics in some important ways. In a study titled Values and Beliefs of Psychedelic Drug Users: A Cross-Cultural Study from Bond University in Australia, it was found that those who have used psychedelic drugs have a statistically significant difference in general life values. It was found that psychedelic users place a higher value on “spirituality”, “concern for the environment”, “concern for others”, “creativity”, and a lessened concern for “financial prosperity” (Lerner and Lyvers 8). This study presents that the psychedelic experience leads to personality changes analogous to Fromm’s idea of the being mode. But, why might a mystical experience cause such a change in values?

One hypothesis is how psychedelics modulate human neurochemistry. Specifically, psychedelics have been found to modulate activity in an area of the brain known as the Default-Mode Network, which is responsible for introspection, contemplation, and self-concept. This finding accounts for the phenomenological effect that the psychedelic experience has; it heightens introspection in a lasting way.

Our egoism leads us to believe that it’s things in the outside world that need to be conquered, when it is the inner world that one should learn to conquer. When we take psychedelics, our shift gazes inward, so to speak. Technically, it modulates activity in the part of the brain called the “default-mode network”. This is the part of the brain that is largely part of our capacity for introspection and self-reflection. Through this modulation of the neurochemistry of attention, we can become more mindful of our own being, rather than preoccupied with our having. This shift into introspection is concurrent with Fromm’s development of the being mode, as well as the findings on the values and beliefs of those who have used psychedelic substance. Spirituality and a lessened desire for financial prosperity are two values that are not held by those in the having mode. But, what accounts for the heightened concern for the environment that psychedelic drug users have?

Another common phenomenon of the psychedelic experience is a “sense of unity with the cosmos”, also known as “oceanic oneness” (Lerner and Lyvers). This can not only deepen our sense of being, but extend it to include the natural environment. When we move closer to seeing ourselves as a part of nature and identifying with the natural world, as a strand in the web rather than the spider on top of it, our behavior towards the nature will profoundly change. Theodore Roszak, author and champion of the Ecopsychology movement, states that “if the self is extended to include the natural world, behaviors leading to the destruction of that world would be experienced as self-destruction” (Roszak). This is a profound notion; if one was to see the natural world as an extended part of who they are, any action that destroys the natural world will be experienced as harm being done to themselves. Psychedelics often produce a profound sense of “unity with nature” in those who ingest them, and this extension of the sense of self to include nature would drastically change that person’s relationship with the Earth. If each person in a society had a profound experience of unity with the natural world as a product of a psychedelic experience, the entire ideological orientation of society would shift. We would see that the Earth is one whole living system in which we are an inseparable part, and that polluting the oceans or cutting down forests is ultimately harmful to ourselves. When we fully realize that we are merely a strand in the web of life, we will be less likely to destroy that web and more likely to act symbiotically with it. Psychedelics may be the most efficient way to realize our connectedness to nature and to bring about the behavioral changes that come with that realization.

In conclusion, it is time that we look at the problem of environmental degradation as a psychological problem, and that the solution to this problem is a shift in consciousness from a fundamentally materialistic and consumerist state of mind to a more spiritual and interconnected one. If Man can focus more on being than having, and if Man can extend his sense of self to include the natural world, we will be a species inclined on preventing the destruction of the Earth, as we would properly equate it with the destruction of ourselves.

Five Lessons from Existential Psychotherapy

As humans, there are fundamental problems that we all face. These problems arise from the very nature of our existence; that we are mortal, impermanent beings who are ultimately alone in our experience of life.

But don’t be depressed about that. Research has shown that realizing certain fundamental truths about the human condition can have valuable therapeutic effects.

Irvin Yalom, author of the landmark textbook Existential Psychotherapy, describes a study that he administered on twenty-six successful group psychotherapy patients. He wanted to find out which outcomes of the psychotherapy sessions were most highly valued by the patients. The patients were given a sixty item Q-Sort test, where they were given cards that had sixty “mechanisms of change” written on them and were asked to sort the cards amongst seven categories from “least helpful” to “most helpful”. These sixty items were developed from twelve “curative factor” categories that each contained five sub-categories, including Catharsis, Self-Understanding, Identification (with members other than the therapist), Family Re-enactment, Installation of Hope, Universality (learning that others have similar problems), Group Cohesiveness (acceptance by others), Altruism, Suggestions and Advice, Interpersonal Input (learning how others perceive them), and Existential Factors.

When the results were analyzed, the results were surprising. Even though the therapists who administered the group therapy weren’t existentially oriented, the Existential Factors category was ranked as the highest in value by the patients. These were the five curative sub-categories:

- Recognizing that life is at times unfair and unjust.

When we are children, our perception of our world is skewed. But, necessarily so. We have faith that when we are hungry, our parents will be there to feed us. We are showered with love, attention and unconditional positive regard. But as we grow older and more of our life becomes out of the hands of our parents’ curation, we realize that we don’t always get our way. Our needs will not always be met as soon as they arise. Our loved ones will not always be within reach. We will not always get what we want when we want it. In our early childhood, we learn these things. But as we get older, our concept of the unfairness of life gets tested even more greatly.

In our teenage years, we often experience the disciplining from our parents as a grave injustice. Whether it be getting grounded, being forced to stay in when all your friends are going out, or being denied the money to buy something that you insist that you need, we experience our concept of how unfair the world is get more tempered and matured by our experience of reality. But as we get older, we experience levels of unfairness and injustice that are not dealt to us by our parents, but by life. Our loved ones might pass away, we could lose our job, our money, our home, or we might get injured or sick, just to name a few of life’s curveballs. But it is important to know that this is a part of our existence. Life is not always fair, and believing that it should be can cause an incredible amount of distress that could ultimately lead to a mental pathology. It may not make the pain caused by life’s unfairness hurt any less, but it will prevent one from creating more pain for themselves by believing that tragedy should not exist. It does. We can either accept that, or deny it, to out detriment.

- Recognizing that ultimately there is no escape from some of life’s pain and from death.

Are often told as we go through life that it is wrong when things go wrong. But this isn’t true. Things will go wrong throughout everyone’s life, and you shouldn’t feel like this is unnatural. Also, if things are going wrong in your life in a way that is causing you pain, believing that you should never experience pain will only cause more of it.

It is also important to recognize that death is the inevitable outcome of life. Most of us will try to deny this. In fact, some psychologists believe that the entire structure of the human psyche is built on top of a foundational denial of mortality. But, this is a truth that we can grasp and internalize as much as we can. Death can happen and will happen to us all. It may be hard to conceive, but embracing that will help you live a more fulfilled life.

There is a valuable idea from Stoic philosophy that pertains to this. Whenever something is causing you pain, ask yourself; is there something you can do about it? If not, then don’t give yourself additional grief. If there is something that you can do about it, then do what you can. Do not cause yourself additional suffering from trying to escape pain that is inevitable. Remember; pain is inevitable, suffering is optional.

- Recognizing that no matter how close I get to other people, I must still face life alone.

We all need a network of friends and family to lean upon, to support and be supported by. Relationships with other people are a crucial part of what constitutes human happiness. Think back to some of the most meaningful moments in your life; chances are, they didn’t happen when you were alone.

Many people, at some point in their lives, will feel the highest amount of intimacy with a romantic partner. This is what many people think a long-term romantic partner is for; to have someone to face the difficulties of life with. Though this is true under many circumstances, such as facing the challenges of raising children, financial troubles, and some emotional difficulties that can be soothed simply by having a hand to hold. But no matter how close you get to anyone, they cannot come inside of your mind to help you face life as an individual. Putting the expectation on others that they can save you from the fundamental burdens of the human condition puts an unrealistic pressure onto them. Ultimately, you must face life alone.

But, with this realization, one can come to adopt a sense of individual responsibility for how they manage themselves in the face of death and impermanence. Adopting responsibility in this way is the first step in developing the psychological toolkit for being existentially resilient.

- Facing the basic issues of my life and death, and thus living my life more honestly and being less caught up in trivialities.

Try this as an exercise; next time you get worked up about any problem in your life, to the point where you get angry and flustered, consider that you might die tomorrow.

Seriously.

You would be very surprised how many problems that arise in life are trivial when in the light of the greater realities of life.

Just take it from Marcus Aurelius;

You can rid yourself of many useless things among those that disturb you, for they lie entirely in your imagination; and you will then gain ample space by comprehending the whole universe in your mind, and by contemplating the eternity of time, and observing the rapid change of every part of everything, how short is the time from birth to dissolution, and the illimitable time before birth as well as the equally boundless time after dissolution.

So maybe, because of facing the basic issues of your existence, you can forgive and release the petty, trivial grudges that you might hold against your loved ones or yourself. The precious and limited time we have in this life is best spent lovingly, because who really knows how much time you have left.

- Learning that I must take ultimate responsibility for the way I live my life no matter how much guidance and support I get from others.

This life is yours to navigate. That realization can come with a flood of anxiety, as this realization of the ultimate freedom to live your life comes with a heavy dose of groundlessness. Other people may offer helpful philosophies for navigating life, and many others may try to convince you that their religion is the best reference to follow in the course of living your life, but you are ultimately responsible for sorting out what is right and what is wrong and acting in light of that. You might be able to lean against the structure that other people impose onto your life, but know that the only structure your life has is the structure that you place upon it.

With much of this advice given through the lens of existential psychotherapy, there is an underlying theme of personal responsibility. We all have a responsibility to face life as it is, to face it alone, to face it in a way that adds to our lives rather than subtracting from it, in a way that allows us to forgive others easily and to live life fully.

Develop this sense of responsibility that you have in the face of the difficulties of human existence, and it will only make you stronger.

How Psychedelics Can Heal Humanity’s Relationship With Nature

All of the different species of life that have ever existed on planet Earth have been confronted with changes in the environment which threatens its survival, and the competency, aptitude and adaptability with which it deals with these changes dictates that species’ effectiveness and favorability as an organism in the grand scheme of life. Our species, Homo sapiens, is facing an environmental crisis. This is not a localized crisis, isolated in a remote part of the world; this crisis is a planetary one. This crisis is a unique one when compared to the environmental cataclysms that have plagued life in the past. Most environmental changes that create hardships for life are caused by some inorganic event; volcanos, asteroid impact, sea level rise, climate change, and the like. Yet the crisis that Man finds himself in right now is one of his own devising. Our behaviors are directly causing catastrophic environmental changes, as the current scientific evidence makes abundantly clear. The life-threatening environmental changes that happened in the past were out of the control of the all those species affected, but Man has the power to avert this environmental crisis if he is able to acquire a new power over his own nature. What could possibly alter the current ideological, moral and ethical state of Man as well as his relationship to his environment, and do it quickly enough that the momentum of our current situation can be diffused before another mass extinction results from our own folly? The answer to this question is currently growing out of countless piles of cow shit across the world. The intelligent and responsible consumption of psychedelic drugs can be demonstrated to be the most efficient and effective way to lead humanity towards a new ethical relationship with the Earth, and ultimately save us from ourselves.

Before I continue, it is important to note how an individual experience can change the collective thoughts and behaviors of a species. Contrary to popular belief, changes at the micro-level can have drastic effects on the macro-level. It is easy to fall into the intellectual trap of thinking that an individual on the micro-level cannot affect something as large as society as a whole on the macro-level. Though, just like how an ocean is a multitude of individual drops, a society is a multitude of individual humans. Though the psychedelic experience is only experienced by the individual under the influence of the drug, and does not affect society in the same way that the introduction of a sports stadium might affect a city, it still affects society as a whole through each individual in that society being influenced by their personal experience. With cultural transformations pertaining to psychedelics, the first occurs with the individual, the second with the social system.

“Psychedelic” is just a word; though it does happen to be the most accepted word for a class of substances that have profound effects on the human mind. There are other words that people have created to define and categorize the incredibly broad effects of these substances, and these words include hallucinogens, psychotropics, mysticomimetics, empathogens, entheogen, and countless other names that attempt to encompass the mysterious effects that these substances have. “Psychedelic” has been the one to stick though; and for good reason. The term psychedelic comes from the Greek roots psyche, meaning mind or soul, and delos, meaning to manifest or to make clear. Psychedelics, in the root sense of the term, manifest the mind. To manifest means to bring up into awareness those contents of the mind which were previously latent, or submerged beneath conscious thought. Though this is just one thought as to what they do or what role they play in the scheme of nature. If one were to take a step back and see these substances in the grand scheme of nature, one would see that they are actually allemones.

An allemone is a chemical that one species produces to influence the growth, reproduction, and survival of another species. The process of communication with said allemone is called allelopathy. The chemical psilocybin, the psychoactive ingredient in “magic” mushrooms, exerts a strange experience amongst animals that consume it. Psilocybin is not the only psychoactive substance which the natural world organically produces that has the mysterious “psychedelic” effect; dimethyltryptamine is another such chemical endogenous to life. It is found in high concentrations in thousands of different plants and animals, including the human brain[1]. Dimethyltryptamine, or DMT, is suspected to be produced by the pineal gland in the brain, and to be the brain’s way of causing dreams during REM sleep. Mescaline, the active ingredient of the peyote cactus used by multiple Native American populations, is also a very powerful psychedelic agent. These chemicals produced by nature may influence us in such a way that is beneficial to our growth, reproduction and survival of a species, the process of which will also be ultimately beneficial to the species who creates these allemones. Even past simply influencing us in a positive way, it may be a way to “allow contact with what we might call the mind of nature”[2], or the “mind of Gaia”[3]. Under the influence of psilocybin or DMT, it is not uncommon to encounter entities or spirits which represent parts of the natural world, or to have incredibly profound and humbling experiences that put into context one’s place amongst the natural world, and we must keep open to the possibility that all the experiences in which these plant-based psychedelics offer are intelligently tailored by nature to influence those who consume it in a way that benefits that species, and subsequently the entirety of the natural world.

How could these experiences induced by these plant-based chemicals have an effect on Homo sapiens in a way that helps benefit our relationship to the environment? One way may be the experience of death that the plant-hallucinogens predictably offer.

“Man is the only animal whose existence is a problem in which he feels he needs to solve” said Erich Fromm, the famous humanist psychoanalyst[4]. We are born into these heart-pounding, breath-gasping, decaying bodies, and this causes us a tremendous amount of anxiety. We exist as animals with a finite existence on this planet, animals that will die and rot in the ground, yet at the same time we house in our psyche a drive for an immortal destiny, a need to assign grandiose meaning to our lives in an attempt to transcend our physical mortality. Ernest Becker, author of the Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death, states that “Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with”[5]. Ernest Becker asserts that the human psyche is in a constant struggle with the reality of death and mortality, so much so that the human condition can be characterized by the active effort to deny all things that face us with the reality of death. Irvin Yalom elaborates on this in his book Existential Psychotherapy, where he says “to cope with [the fear of death], we erect defenses against death awareness, defenses that are based on denial, that shape character structure, and that, if maladaptive, result in clinical syndromes. In other words, psychopathology is the result of ineffective modes of death transcendence”[6]

Examples of how the human capacity to deny mortality can be demonstrated through many cultural taboos. One such example is the censorship of sexuality which, to varying degrees, is present in every known human culture. Breastfeeding in public is a very present taboo in our society, as well as the censorship of female breasts in general. Male nipples are also censored in society; almost all children cartoons show shirtless male characters with an absence of nipples. We seem to be the only animals that hide and censor our genitals and sexual organs, and this is due to the fact that human beings are the only animals who are ashamed of sexuality, as genitals and the need to sexually reproduce are symbols of the fact that we are mortal animals. Angels and gods are always depicted as not having genitals, because it is engrained in religious mythology that divine beings have transcended mortality, and have thus transcended the need to sexually reproduce. The act of sex is as characteristic to animals as is eating and defecating, two other things that divine immortal beings have no need to do. We long to be immortal, so we create and idolize transcendent and immortal mythic figures that represent the highest aspirations of the human species.

Humans are also the only animals that shave the hair off of our face and bodies in an attempt to be more attractive to the opposite sex. Hairlessness is a desirable trait in the sexuality of the human species; which may explain why we are the only hairless ape, or what Desmond Morris calls “the naked ape”[7]. Shaving the hair off of our face and body is an obvious denial of our animal nature, literally removing traces of evidence that we have small patches of hair of the same like as chimpanzees. We also are the only animals that disguise and place a sensory façade over our natural body odor; we use deodorant and perfumes to overpower the natural smell of our pheromones which are naturally useful to subconsciously communicate genetic information and to find genetically compatible sexual partners. Another mascot of the denial of our animalistic mortality is the blatant denial of the processes of urination and defecation. Humans are the only animals that must hide behind locked doors to feel comfortable enough to defecate, as the act of defecation is an animal act, and thus a mortal act. The human propensity to feel shame about defecation and urination is thus another way in which we try to escape and deny our own animalism.

How is this denial of death affecting the human relationship to the environment? It is quite simple, actually. Humans want to believe that we are not animals; that we are not beings that are doomed to blindly and dumbly rot in the ground and disappear forever. Because we so strongly desire to be something which we are not, we reject and push away everything that hints at the reality which we do not want to see. Because we don’t want to believe we are mortal as is the rest of nature, we push away and turn nature into the other. This othering creates a fundamental disconnection between humans and the natural world, as we crave to believe that we are something separate from it, and subsequently not subjected to the reality of mortality which curses all living things. This othering of the animal allows us to literally dehumanize the animal world, which allows us to reason our negative actions towards the environment which may cause ecological stress or even eventual extinction of certain animals that live in the areas which we choose to exploit. How can psychedelics help dissolve this human propensity to turn nature into the other?

Psychedelics help decondition our fear of death through offering the experience of death. “A fear must be experienced before it can be reduced or destroyed”[8], and the plant-psychedelics reliably induce the experience of death. In terms of treatment of death anxiety, the most important component of the psychedelic experience is the religious “sense of oneness and unity with the universe”[9]. This is often called ego-transcendence, and is the primary factor of the psychedelic experience that alleviates death anxiety. This experience is characterized by the loss of the body and the sense of self, as “ego identification and ego boundaries are weakened”[10]. If a human holds the belief that they are nothing more than their body and do not exist outside of their body, death entails the destruction of everything we perceive ourselves to be; true death. This mindset is anxiety-producing to an individual because through this interpretation, death is seen as the true end of one’s existence. When the fear of death is dissolved, it is usually done so through a deep realization of cosmic unity. This sense of cosmic unity compels one to identify themselves with the universe as a whole compared to just their ego. The patient transcends their ego, and death anxiety is alleviated because the patient is left with a profound revelation that they are one with the universe. In other words, “the person becomes very much aware of being part of a dimension much vaster and greater than himself”[11]. When this revelation is had authentically through the psychedelic experience, death is seen as a transformation rather than an end. This alleviates, dissolves and allows one to transcend the innate death anxiety that characterizes the human condition, the anxiety which causes humans to create a psychological disconnect between us and the other animals. The experience of death allows us to lose the anxiety associated with death, and brings us closer to fully realizing that we are just another animal in the kingdom of life, and would make Man less apt to see himself as something separate from nature; a separateness that allows us to dominate and destroy nature.

When we move closer to seeing ourselves as a part of nature and identifying with the natural world, as a strand in the web rather than the spider on top of it, our behavior towards the nature will profoundly change. Theodore Roszak, author and champion of theEcopsychology movement, states that “if the self is extended to include the natural world, behaviors leading to the destruction of that world would be experienced as self-destruction”[12]. This is a profound notion; if one was to see the natural world as an extended part of who they are, any action that destroys the natural world will be experienced as harm being done to themselves. Psychedelics often produce a profound sense of “unity with nature” in those who ingest them, and this extension of the sense of self to include nature would drastically change that person’s relationship with the Earth. If each person in a society had a profound experience of unity with the natural world as a product of a psychedelic experience, the entire ideological orientation of society would shift. We would see that the Earth is one whole living system in which we are an inseparable part, and that polluting the oceans or cutting down forests is ultimately harmful to ourselves. When we fully realize that we are merely a strand in the web of life, we will be less likely to destroy that web and more likely to act symbiotically with it. Psychedelics may be the most efficient way to realize our connectedness to nature and to bring about the behavioral changes that come with that realization.

In conclusion, psychedelic substances are incredibly powerful and mysterious chemicals that assert a powerful and profound impact on the human psyche, and the intelligent use of these substance may cause certain changes which will collectively shift humanity in ways that influence our species to behave more ethically towards the natural world. These chemicals may very well be powerful teachers that evolved specifically to function as such, as a way to learn from the mind of Gaia. These substances could help absolve humanity from our inherent denial of mortality and help us accept death, and help rid us of our othering of the natural world on the basis of our subconscious rejection of the reality of death that our animal nature entails. The profound effects of the psychedelic experience could also shift our sense of self to include the natural world, and thus lead us to treating the health of the Earth as we would treat the health of our own bodies. These incredible substances may very well be the catalysts that change the ideological state of our species and bring us closer to a new Earth ethic.

[1] Rick Strassman, DMT: The Spirit Molecule (Rochester: Park Street Press, 2001), 31.

[2] Paul Devereux, Whispering Leaves: Interspecies Communication? (San Francisco: Disinformation Books, 2015), 78.

[3] James Lovelock, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), ix.

[4] Erich Fromm, “The Psychological Problem of Man in Society” in On Being Human, (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 1997), 32.

[5] Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (New York: The Free Press, 1973), 15.

[6] Irvin Yalom, Existential Psychotherapy (New York: Basic Books, 1980), 27.

[7] Desmond Morris, The Naked Ape (New York: Dell Publishing Co, 1967)

[8] Michael Mithoefer, MD “MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy: How Different Is It from Other Psychotherapy?” in Manifesting Minds (Berkeley: Evolver Editions, 2014), 126.

[9] Lerner, Michael, “Values and Beliefs of Psychedelic Drug Users: A Cross Cultural Study” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (2006), 150.

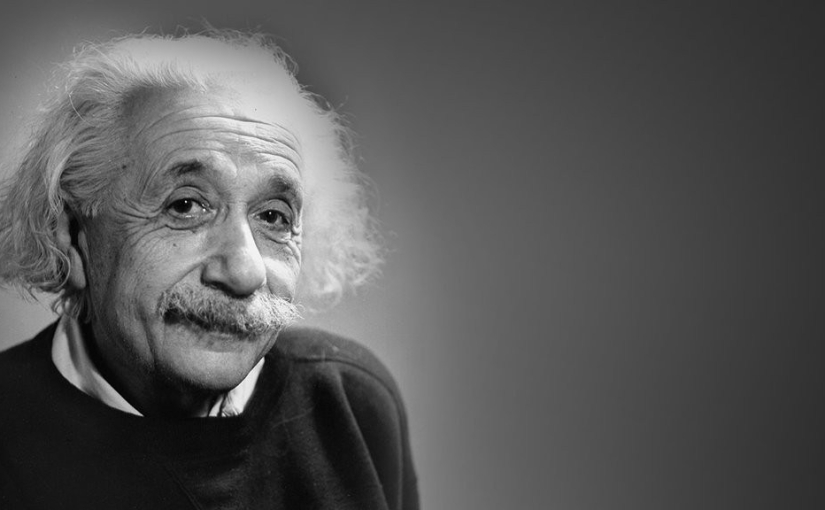

Albert Einstein and the Religion of Mystery

There have been few thinkers in modern history who have been as influential as Albert Einstein. Even today, his words serve as some of the most valuable philosophical testaments on subjects such as love, imagination, non-conformity and religion.

Albert Einstein often expressed his distaste for classical religion, calling those who believed in life after death “feeble souls”. Belief in an all-powerful god, for Einstein, was the result of “fear or ridiculous egotism”. Though this does not mean he did not consider himself a religious man. Einstein rejected the term “atheistic”, and preferred the term “religious non-believer” for his religious views. He was religious, but did not believe in any religion. What did he mean by this?

In one of his most poignant essays, published in 1931 for Living Philosophies, he explains.

“The most beautiful thing that we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed. This insight into the mystery of life, coupled though it be with fear, has also given rise to religion. To know what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty which our dull faculties can only comprehend in their most primitive forms- this knowledge, this feeling, is at the center of true religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I belong in the ranks of devoutly religious men.”

Einstein expresses that it is the sense of mystery that sits at the heart of true religiousness. This is a sentiment that is echoed by Ram Dass, philosopher and psychedelic renegade of the mid-to-late 20th century:

“Every religion is the product of the conceptual mind attempting to describe the mystery.”- Ram Dass

When looking at the function of religious mythology, it becomes clear that it has been formed in reflex to a sense of mystery. But where Einstein stands rapt in awe, other religions try to provide answers that extinguish the mystery, and the fear coupled with it.

Why are we here? Where did life come from? Where is life going? What happens upon death?

It is these questions that are the most mysterious to humans; they are also the questions that virtually all religions answer.

But the sense of mystery for Einstein does not come from these existential questions.

“To ponder interminably over the reason for one’s own existence or the meaning of life in general seems to me, from an objective point of view, to be sheer folly.”

He did not need to ponder these questions to feel a sense of mystery. For Einstein, this sense of religious mystery came upon his appreciation of the universe itself.

“It is enough for me to contemplate the mystery of conscious life perpetuating itself through all eternity, to reflect upon the marvelous structure of the universe which we can dimly perceive, and to try humbly to comprehend even an infinitesimal part of the intelligence manifested in nature.”

Perhaps a prescription from Einstein on how to experience the divine could be expressed in two words; Seek mystery.

Source: Living Philosophies, Simon & Schuster, 1931, New York.

Trance States and the Emergence of Prehistoric Art

The artist’s mission is to make the soul perceptible. Our scientific, materialist culture trains us to develop the eyes of outer perception. Visionary art encourages the development of our inner sight. To find the visionary realm, we use the intuitive inner eye: the eye of contemplation, the eye of the soul. All the inspiring ideas we have as artists originate here.

–Alex Grey, The Mission of Art

It is a quality of evolutionary inquiry to look deep into the past to develop a deeper understanding of the present. This is done by developing a causal link between those crucial stages of development in the past and how human beings have snowballed from those early stages into the advanced species that we are today. One of these idolized advancements is the production of art; it is one of those few things that distinguish humans from other animals. Some scientists go so far in suggesting the name “Homo symbolicus” (Froese, 2013, p. 199). What a strange animal we are, erecting some of the largest buildings in our urban centers and dedicating them to the display of these artistic productions. It is in art that we find meaning, symbolism, expressions of feelings that capture and resound the human condition so that we may feel, if only for a moment, that we are not alone in our navigation through life. How did art come into being? What stimulus knocked over the first domino in the evolution of the human artistic capacity and led us to become the image-making species which we are today? This paper offers an answer to this question; that it was from the facilitation of trance states that an internal imagery surfaced, serving as the first subject matter for human beings to artistically reproduce in the external world.

First, it is important to define a key term in this research; trance state. A trance state, also referred to as an altered state or altered state of consciousness, refers to the wide variety of psychological states separate from the normal, alert, problem-solving states of consciousness (Kjellgren 2010). Trance states can be intentionally facilitated through a variety of means, such as hypnosis, holotropic breathwork, psychoactive substances, long-term fasting, sensory deprivation, as well as shamanic styles of music and dance (Hancock, 2005).

Why does art exist, and what was the stimulus that caused an organism such as humans to create it? This is a question that scientists, philosophers, anthropologists and mystics have been trying to answer for hundreds of years.

In the beginning of the anthropological work done on the origins of cave art, it was posited that these images were meaningless products of humans who had reached the point of evolutionary fitness wherein they had a large surplus of time to spend on tasks that had no survival function. This explanation stemmed from early notions of the “savage man”, where anthropologists looked at early humans as crudely primitive sub-versions of ourselves, and this theory became known as art pour l’art, or art for art’s sake (Lewis-Williams, 2002). The notion that this art came from nothing but leisure time and aesthetic sensibility is not supported by the locations in which much cave art is found; many pieces are found not only deep in pitch dark caves, but deep in thin tunnels in which only one person can squeeze into at a time. This supports the notion that early people were creating these works of art not to be looked at for some type of aesthetic sense, but rather made from a creative urge accompanied by a deep personal significance imbued in the design by the artist who made it. The artist was making it for themselves.

Another explanation of early cave art is that these are simply reproductions of the external environment. This may be supported by the examples of animals represented in many examples of cave art, but this explanation falls short in explaining many other examples. Many pieces contain geometric imagery such as parallel and zig-zag lines, spirals and lattices; things that “early humans could not have seen in the natural environment” (Lewis-Williams, 2011, p. 7). Many other pieces contain half-man half-animal hybrids, called “therianthropes” (Lewis-Williams, 2005, p. 45); again, this is not something that one would see on a stroll through the forest.

David-Lewis Williams, Professor of Cognitive Archaeology and Director of the Rock Art Research Unit in the Department of Archaeology at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, was the first to propose the neuropsychological model of cave art. Lewis-Williams made the connection between form-constant imagery, trance states and the patterns seen in cave art.

The crucial research that serves as the foundation of the Lewis-Williams’ neuropsychological model of cave art is that done on form-constants. Form-constants are the basic reoccurring geometric patterns seen in hallucinatory trance states. The first research done on this phenomenon was by Heinrich Kluver, who categorized these patterns into four basic forms; (I) tunnels and funnels, (II) spirals, (III) lattices, including honeycombs and triangles, and (IV) cobwebs (Bressloff, 2002). It was after further research that two more categories were discovered, which are (V) dots and (VI) zig-zags (Froese, 2013). These basic recurring patterns of hallucination derive from the biological structure of the nervous system, which is why all humans experience these patterns. Because they derive from the human nervous system, “all people who enter certain altered states of consciousness, no matter what their cultural back ground, are liable to perceive them” (Lewis-Williams, 1998, p. 13).

This basic form-constant imagery constitutes the first stage in Lewis-Williams’ Three Stages of Trance model of cave art, which is based off research done on the phenomenological effects of mescaline. This imagery is the first that is experienced in the duration of visionary trance states, and are often the only visuals achieved in minor trance states, as would be brought about by a low dose of a hallucinogenic drug. These patterns are seen universally in ancient art across space and time as they are emergent of the human biology and culturally-independent. These patterns arise in the First Stage of Trance, and are found in many Paleolithic cave art sites around the world, including the world’s oldest known piece of art found in the Blombos cave in South Africa, estimated to be about seventy-seven thousand years old (Clottes, 2009)

It is in the Second Stage of Trance, as suggested by Lewis-Williams, that these geometric form-constants give way to what are called “iconic forms” (Lewis-Williams, 1988, p. 203). In this stage, the brain takes these fundamental Stage 1 patterns and uses them as building blocks to form objects that are culturally-dependent. A zig-zag line may turn into a snake, or a spiral may turn into a sea shell in this process. This happens as “the brain attempts to recognize, or decode, these forms as it does impressions supplied by the nervous system in a normal state of consciousness” (Lewis-Williams, 1988, p. 203). This is like the phenomenon of a person walking through a forest and being startled at the sight of what they believe to be a snake, when upon further inspection, it is only a stick.

After the second stage, participants report the experience of traveling through a vortex or tunnel and proceed to have hallucinations characterized by three-dimensional scenery and encounters with entities, most often in the form of therianthropes (Lewis-Williams, 1998, p. 204). Therianthropes are beings that are half-man, half-animal, and are found depicted in many cave sites, yet are most concentrated in caves in central Europe and South Africa (Clottes, 2009).

These stages of the hallucinatory experience are reflected in all the earliest forms of art, and support the notion that early artists were reproducing the hallucinations that occur when the nervous system is triggered into a trance state. It is through Lewis-Williams’ research that the connection between hallucinations and the subject matter of cave art became evident. But how were early humans having these hallucinatory trance experiences?

One method that has been used by humans to alter consciousness is the ingestion of hallucinogenic plants and fungi. “Consumption of these substances is as ancient as human societies themselves” (Guerra-Doce, 2014, p. 752), and there is evidence to support that these compounds held great importance for early people, as there have been Paleolithic burial sites discovered that contained psychoactive compound buried with the body. The compounds that produce visionary trance states are known as psychedelics, and produce minor to drastic changes in perception and alterations of consciousness. It was with the psychedelic compound mescaline that many of the early studies of form constants were done, and users dependably reported form-constant imagery and all three stages of the Three Stages of Trance model.

There are many modern examples of psychedelically-influenced art representing form-constant imagery, as well as therianthrope entities. The use of ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic tea, is still very prevalent amongst people in the Peruvian Amazon who “speak of an initial stage in which ‘grid patterns, zigzag lines and undulating lines alternate with eye-shaped motifs, many-colored concentric circles or endless chains of brilliant dots” (Frecska, 2012, p. 44). These descriptions mirror both modern hallucinatory phenomenon done in laboratory settings as well as examples of Paleolithic cave art.

Another potential method used by early humans to achieve a visionary trance state is the use of music and dance. There are modern examples of music and dance being used by hunter-gatherer tribes in the Kalahari Desert as the principal means to reach trance states, and it is thought that the way of life that these people live has been relatively unchanged for millennia, giving us a window on how ancient peoples may have facilitated trance states (Hancock 2005). It is speculated that these “long hours of dancing combined with exhaustion, dehydration and fatigue” can trigger altered states of consciousness by placing the body under intense stress (Hancock, 2005, p. 122).

One study titled “Altered States During Shamanic Drumming: A Phenomenological Study” published in the International Journal of Transpersonal Studies investigated the effects of shamanic-style drumming on consciousness. In the study, twenty-two participants were gathered in a dimly lit room and led through a shamanic-style drumming meditation. The session included live rhythmic drum beats that lasted twenty minutes in duration, all while the participants were laying down with their eyes closed. Afterwards, written reports were taken from the participants and qualitatively analyzed. Many participants reported having visual hallucinations and alterations in normal states of consciousness. Among the most common and most intensely felt experiences were “insight”, “landscapes”, “encounters with animals” and “the tunnel” (Kjellgren, 2010, p. 8). Some of these phenomenological experiences are parallel to the experiences of participants who had ingested mescaline in a laboratory setting, namely the experience of a tunnel and the imagery of a three-dimensional landscape accompanied by entities.

Sensory deprivation is another dynamic that can trigger a trance state in human beings, and early cave painters could have facilitated “sensory deprivation in the caves themselves” (Hancock, 2005, p. 90). Sensory deprivation causes hallucinations through depriving the brain of external stimulus, causing the brain to generate its own. The output of this inwardly-generated imagery would follow the form-constant patterns, and would give early painters in the pitch-black caves visual hallucinations seemingly projected in front of them. Perhaps the geometric hallucinations seen in caves were the cave painter’s attempt to trace the hallucination, or to capture the transient visual in a lasting form.

Psychedelics, shamanic music/dancing and sensory deprivation are all ways in which the human being can come into a trance state and release the imagery embodied in the nervous system, but it is possible that these methods were used in combination with each other. The ceremonial ingestion of psychedelic substances may have been used in combination with shamanic trance dancing, allowing early people to reach peak trance states. It is also possible that psychedelics were ingested before entering the caves, heightening the hallucinations triggered by sensory deprivation.

It is evident that these methods could have been used by early people to facilitate visionary trance states, but how might this have aided in the evolution of the capacity through which humans produce art? Though some may have reached these visionary trance states and reproduced their hallucinations, it is possible that there were other humans who took no part in these modalities of altering consciousness. The behavior of reproducing images generated by the imagination could have spread as a meme, and other humans could have mimicked those who were driven to create art because of their hallucinations. In this sense, trance states may have injected the behavior of creating art into human culture, allowing this meme to evolve into what it is today.

In conclusion, there is a compelling amount of evidence to support the notion that the first images created by humans are reflections of our neurology, images embodied into the human brain and brought out during hallucinatory experience. This argument places a new importance on altered states of consciousness, and suggests that these states are not something to be scoffed at or denounced; we may owe our humanity to them.

The 7 Flawed “Lessons” of Modern Education

“Compulsory government schooling has nothing to do with education” says John Taylor Gatto, author of Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling. Gatto makes the case that the current government-mandated school system has so many inherent flaws in its design that the entire institution must be replaced. Gatto would know; he worked as a New York City public school teacher for 30 years. “Over the years,” Gatto says, “I have come to see that whatever I thought I was doing as a teacher, most of what I was actually doing was teaching an invisible curriculum that reinforced the myths of the school institution and those of an economy based on caste.” Gatto reveals the seven “lessons” that exemplify the flaws that permeate the public school system, flaws that are inherent in its design.

- Confusion

There is no sense of coherence between the subjects taught in public schools. “Everything I teach is out of context” says Gatto. “I teach too much; the orbiting of planets, the law of large numbers, slavery adjectives, architectural drawing, dance, gymnasium, choral singing… What do any of these things have to do with each other?”

The lack of continuity and coherence in the public school system causes anxiety and panic in children, as the curriculum is in constant violation of natural order and sequence. We are led to believe that the array of subjects taught to students throughout the day will give them a well-rounded education, but this violates how humans learn. Children cannot learn in an environment of fragmented facts. There needs to be a sense of continuity and interrelatedness between all subjects taught in school, as that is how the mind develops a schema of the world; an associative net of information from which the mind can derive meaning. Currently, subjects are being taught in a way that doesn’t allow the student to connect information, leaving them with a mix-match of unintegrated facts and concepts.

- Class Position

Children in public school are separated into different classes with varying positions, teaching that society runs on a caste-like hierarchy. “If I do my job well,” says Gatto, “the kids can’t even imagine themselves somewhere else because I’ve shown them how to envy and fear the better classes and how to have contempt for the dumb classes.” Rather than having a class structure that allows for a students’ potential to unfold upon a level playing field, they are taught at a young age that their potential has a place either below or above others. “The lesson of numbered classes is that everyone has a proper place in the pyramid and that there is no way out of your class except by number magic. Failing that, you must stay where you are put.”

- Indifference

“Indeed, the lesson of bells is that no work is worth finishing, so why care too deeply about anything?”

Students are expected to show interest and enthusiasm about the subject being taught at a given time, yet are expected to completely shift themselves to a new subject at the sound of a bell. This doesn’t allow learning to take its natural course. Children are being led down a rabit hole of information only to be pulled out and thrown down a new one at the sound of a bell. “They must turn on and off like light switches” Gatto writes. “Bells destroy the past and future, rendering every interval the same as any other, as the abstraction of a map renders every living mountain and river the same, even though they are not. Bells inoculate each undertaking with indifference.”

- Emotional Dependency

“By stars and red checks, smiles and frowns, prizes, honors, and disgraces, I teach kids to surrender their will to a predestinated chain of command” Gatto writes, as he explains how children are taught to be emotionally dependent on their teachers. Teachers also serve as disciplinarians, deciding what behavior from the students is to be rewarded and which is to be punished. Students must conform their behaviors to those preferred by their teachers as they depend on the teacher’s favors, such as going to the bathroom and getting a drink of water. There is a pressure on the children coming from the school to be emotionally homogeneous. “Individuality is constantly trying to assert itself among children and teenagers, so my judgements come quick and fast. Individuality is a contradiction of class theory, a curse to all systems of classification.”

- Intellectual Dependency

“This is the most important lesson of the all: we must wait for other people, better trained than ourselves, to make the meanings of our lives.”

Students in a classroom are presented with an authority figure; the teacher. The teacher is not just an authority in a disciplinary way, but an intellectual way. If the teacher says it, it is true. This is a central precept for children in school who are never taught how to think critically, only how to absorb information with the least amount of resistance. If a student does not accept and internalize the information given to them by the teacher, they will be given low grades. As children are taught to deify good grades and demonize bad grades, this instills incentive in the children to internalize the information that will lead to the higher grades. This channels all of the students’ attention into the teacher’s curriculum. “Of the millions of things of value to study, I decide what few we have time for… curiosity has no important place in my work, only conformity.”

This “lesson” of intellectual dependency is central to a population that keeps certain economic pillars in our society strong, Gatto argues. “Think of what might fall apart if children weren’t trained to be dependent… Commercial entertainment of all sorts, including television, would wither as people learned again how to make their own fun. Restaurants, the prepared food industry, and a whole host of other assorted food services would be drastically down-sized if people returned to making their own meals rather than depending on strangers to plant, pick, chop and cook for them. Much of modern law, medicine, and engineering would go too, as well as the clothing business and school teaching, unless a guaranteed supply of helpless people continued to pour out of our schools each year.”

- Provisional Self-Esteem

“If you’ve ever tried to wrestle into line kids whose parents have convinced them to believe they’ll be loved in spite of anything, you know how impossible it is to make self-confident spirits conform.”

Gatto describes how the school system uses a child’s self-esteem to direct their behavior through placing selective pressures on their development. Progress reports are sent home to a child’s parents that either show approval, or, down to a percentage point, disapproval of the child’s performance in school. This progress report shows, as Gatto writes, “how dissatisfied with the child a parent should be”. Children come to depend on the judgement of others to make an evaluation of their own self-worth as they are taught that their worth is dependent on these “expert” judgements. Self-esteem is not sourced from virtue, integrity, compassion and empathy, but from academic conformity. “The lesson of report cards, grades, and tests is that children should not trust themselves or their parents but should instead rely on the evaluation of certified officials. People need to be told what they are worth.”

- One Can’t Hide

Almost every square foot of modern schools is under video surveillance, if not under the surveillance of a watchful hall-monitor or teacher. There is no private time. Some of us may be able to remember moments in middle school or high school when the teacher had to step out of the class for a few minutes, leaving the students in the room for a moment. Most remember the anxious response coming from that; anarchy. Students are so used to being under surveillance that the moment they are not, they feel as if the structure of school itself has become groundless.

Schools must also constantly keep tabs on the students to ensure that there is no collaboration or communication going on that is not approved of. “Children will follow a private drummer if you can’t get them into a uniformed marching band.” Placing children under constant surveillance and stripping away all privacy ensures that their conformity is only to that which the school puts in place.